Remote Miniatures Gaming: Understanding the Basics

Action around Kidney Ridge in 28mm/1:48 scale, as viewed through a wireless security camera during remote play.

Action around Kidney Ridge in 28mm/1:48 scale, as viewed through a wireless security camera during remote play.

Many of us have spent years of spare cash and free evenings raising our miniature armies, and suddenly, with the arrival of the pandemic, they are sitting in their boxes and collecting dust. The collection of miniatures is a core part of the hobby, and is itself rewarding, but at the end of the day we all want to see our figures take the field, whether in triumph or ignominy.

Many miniatures wargamers are resigned to waiting the pandemic out, hoping that in weeks, months, or years we will be able to go back to our hobby as we have always known and loved it. At some point, this will happen, but until then it is still possible to run games with your miniatures collection, using common technology and with remote opponents. It may not be as good as the real thing, but it is a way of carrying on until the situation improves, and it lets you use those figures you have invested so much in.

There are some alternatives to using actual miniatures for playing remote "miniatures" wargames, and some of these are becoming popular. Among our community, people have used Tabletop Simulator with success, especially for 1-on-1 games. That type of system is fine, but it isn't gaming with actual miniatures. It is a matter of personal taste, but some of us prefer to see the real thing in action, even if it is through the lens of a camera, rather than a video-game-like representation of it. This article describes only the use of actual miniatures, and leaves guidance about how to run remote games with virtual miniatures to others.

This form of remote wargaming with actual miniatures seems to be increasing in popularity, alongside purely virtual approaches. It can be done with relatively inexpensive equipment, and with technology which many people use every day. This article is based on the experiences of an informal community of gamers based in (mostly) southern New England, but one which seems to be growing both geographically and in size at a fairly good clip. At this point, we have run several dozen games using the techniques described.

First we will provide a "how-to" description of our techniques, and then we will discuss some things we have learned through trial-and-error. For us, this was a new way of gaming, and we didn't get everything right the first time out, but we have managed to play a lot of enjoyable games, and we continue to do so. Some useful resources will also be listed, as this is a new and evolving approach to the hobby.

If you have ever used Skype or Zoom (or GoToMeeting or Bluejeans or Teams or any of the other, similar tools) to participate in virtual business meetings, then this approach will be quite easy to understand: instead of looking at a head-shot of the speaker during a virtual meeting, you will be looking at a camera showing the wargames table, and talking your way through a virtual gaming session. (It is amazing how much more fun Zoom and Skype are when you are busy killing toy soldiers with other toy soldiers, instead of doing work!)

This does present some challenges: the web cams which come with your standard laptop these days are optimized for providing a view of the speaker's face, and the video-conferencing software by default shows the face of whoever is speaking, through their camera. This does not work when you want to be looking at a wargames table (and not at the faces of your wargaming buddies).

These types of software do give you the abillity to determine what is shown on the screen, however, using the features which business people often use to review documents, see Powerpoint presentations, and so on: screen-sharing. By screen-sharing a camera going through the computer which is situated where the wargaming table is, everyone can get a view of the table, allowing them to talk their way through the game without constantly seeing each other instead. Everyone who is playing remotely will have the same view of the proceedings, which means that even if it is non-optimal, at least it is a level playing field!

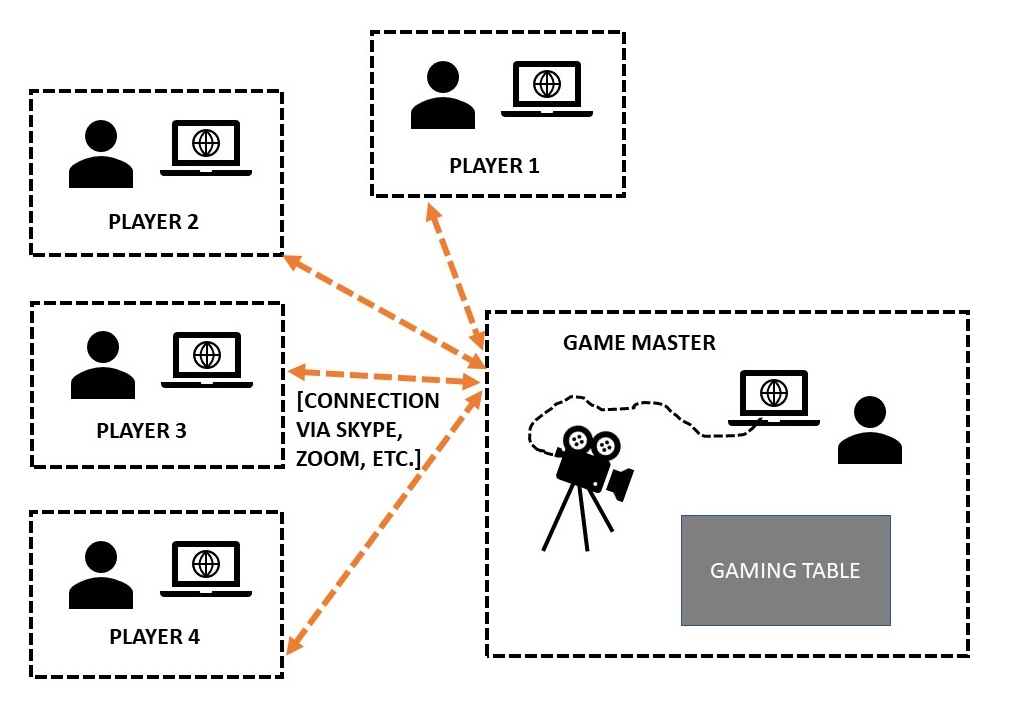

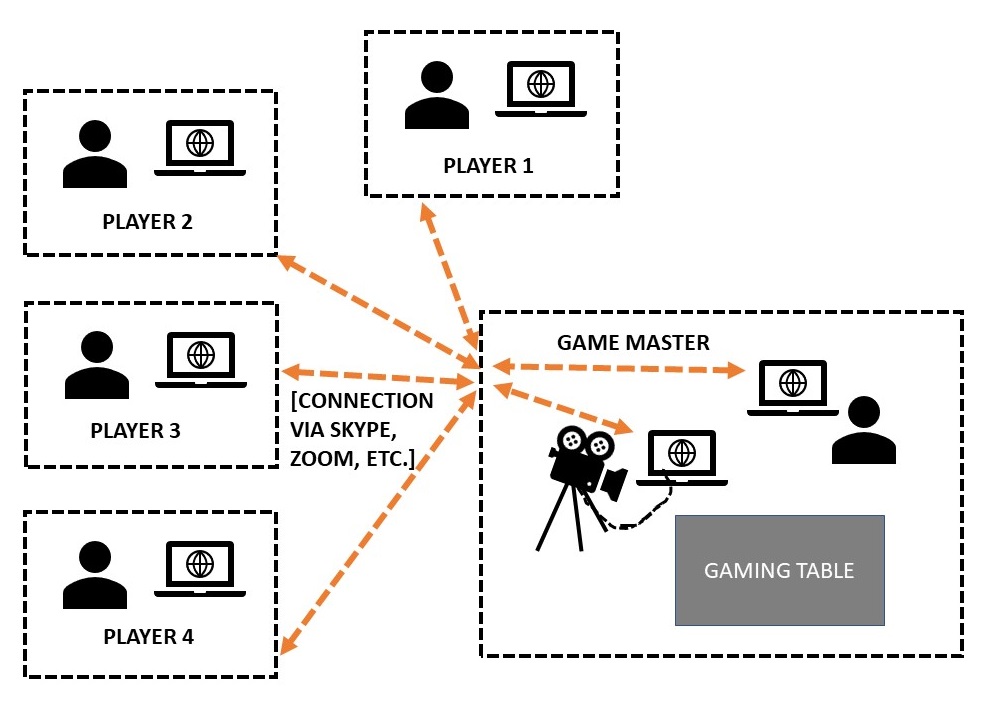

Obviously, the person who is in the same room with the table and miniatures has an advantage, and we have found that it is best when the player who is hosting the event - that is, the one with the table and miniatures being shown through the camera, and shared with everyone else - acts as the Game Master. Their job is to moderate the game, and to make moves for the players as they dictate. The diagram below shows how this is set up:

There are several things to note here, and they may seem obvious, but to older wargamers who are not very tech-savvy they may not be, so bear with me.

First, there is exactly one camera in this set-up. It is at the Game Master's location, which also where all of the figures and terrain are, set up on a single wargames table. The players can also have cameras - and many will, built into their computers and devices - but they are not required. The absolute requirement is for at least one camera giving a view of the action on the tabletop. (It is possible, and sometimes desireable, to have more than one camera, but it is not absolutely necessary - see the discussion below).

While there may only be one camera, each player will require a device or computer which has a microphone and speakers. If these are missing then they will be unable to talk to the Game Master or other players. Most devices these days have microphones and speakers built in, as do most laptop computers, but desktop computers may not. A headset can be purchased at Amazon for quite a reasonable price, and at many other places online, as can regular speakers and a microphone (although these may be more expensive). Headsets can become irritating to wear after a couple of hours, so it may be worth spending a couple of extra bucks, but they also help to cut down on background noise. Depending on your home situation while remote gaming, this can be a factor.

When it comes to figures and terrain, these must all exist at one location: the Game Master's. This can be limiting, because the Game Master must own all of the figures needed for any given game. (We have not found this to be a problem, since most of us run games at the local conventions and own all the necessary bits and pieces). While you can have duplicate game boards going, this seems too limiting to us, as it requires multiple people to have matching sets of figures and terrain. (We find that sending out maps and scenario descriptions allows for a sufficient degree of understanding of what is happening, even though it is more limited.)

There are some important considerations regarding miniatures and terrain, and how they are set up - these will be addressed below in their own sections.

The orange arrows indicate that all of the players are connected in a single Skype "call," "chat," "group," or Zoom "meeting." (There are many different names for what is effectively the same thing, depending on what software service and features you use to do it.) We will discuss the specifics of how to do this below - at least the way we do it.

This diagram will serve as a point of reference as we discuss various topics.

The key piece of equipment here - and one which you may need to purchase - is a camera which can provide a view of the tabletop. There are two simple options which we have found that are reasonably easy to set up and use. (It is certainly the case that there are many different ways to get a camera view of the tabletop for gaming purposes, and we have read about some quite sophisticated ones. We are limiting ourselves here to the easiest ones to get started.)

The first technique is for those who already own iPhones or Android smartphones. Many of these phones have very good cameras in them, and require only a suitable stand so that they can be positioned and aimed at the tabletop properly. (You can buy a flexible tabletop tripod with a universal phone mount for less than $10.00.) The smartphone cameras give you the ability to zoom the picture, and many produce a high-quality image. Because the smartphone can go directly onto the Internet, you can add it to the game with its own account (see below) and then share the screen directly from the phone.

Note that - in reference to the diagram above - the smartphone is directly connected to the Skype or Zoom session through its own internet connection (wireless network or 4G/5G), and can thus be used both as the connecting device and the camera in one compact package. (It may be preferable to actually use a separate account for the Game Master to connect to Skype/Zoom, and give the camera its own account, so that the Game Master can see what players see - this is dicussed below).

This approach has some advantages, not least of which is that, if you already own such a phone, you already have the camera you need - you can avoid spending much money at all. The image quality from smartphones can be very good, too - iPhones are expensive, but they have excellent cameras (we have used iPhone 7s and 10s with good results, and Android phones, too - see the pictures for some examples).

There are also some potential downsides to this, however: the cameras in iPhones and Android smartphones require good lighting, and often do not have a particularly wide angle of view (although iPhone 10 cameras are better than iPhone 7). This means that during play, if you are using only a single camera, it may need to be moved quite a bit as troops maneuever, which can be distracting and annoying to players. With games that use a small table (4 x 4 feet or 4 x 6 feet) this is generally not bad. For a larger table it can be more problematic. For those who do not have a lot of gaming space, this is often the best approach to use, because a smartphone can be positioned either on one edge of the table, or on a taller tripod very close to it.

The second approach uses a wireless security camera to give an overall view of the tabletop. Such cameras are relatively inexpensive, ranging from $25 - $60 USD on Amazon at the time of writing. The one you want should have a 1080p resolution, and should be something which can be connected to wirelessly using a separate computer or device (this will need to be the computer/device the game master uses to run Skype or Zoom). Such cameras are used for outdoor secuity, and generally have wide angles of view, and are equipped to handle low-light environments. The software used to monitor them generally provides the ability to pan and zoom, which is very useful during games, as the view on the tabletop can be changed by the game master without physically moving the camera. Similar cameras meant for indoor use - "nanny cams" - have many of the same features.

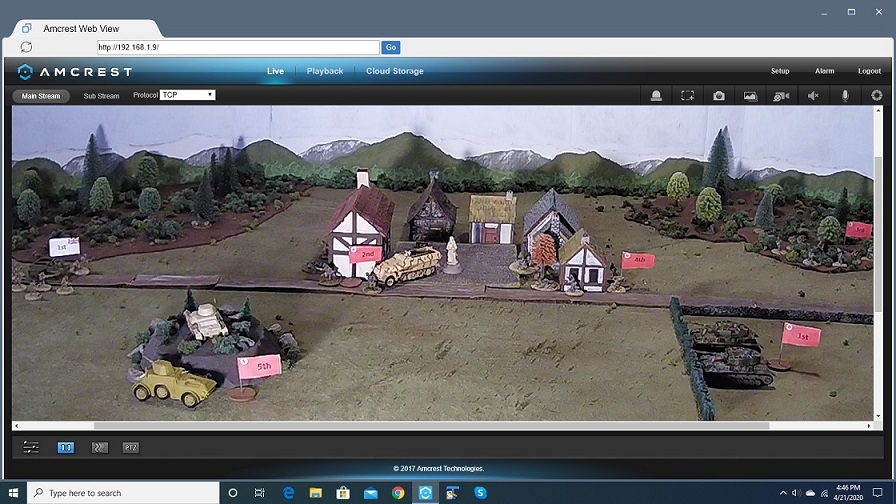

I have personally had a good experience using an Amcrest 1080p HDPro security camera, which has a browser plug-in that lets me monitor and operate the camera directly from my regular computer, which is the machine I use to run Skype during games. I simply screen-share the monitor window (see below).

There are (much) more expensive cameras which can be directly connected using a USB port, and which have "PTZ" (pan, tilt, zoom) built into them, designed for use in corporate video-conferencing facilities. These are great, but they usually run hundreds of dollars. A newer technology called "EPTZ" (electronic pan, tilt, zoom) is now becoming available in some USB cameras, and these would be perfect, but the price point is still much higher than for wireless security cameras or nanny cams (the cheapest I have seen is around $100 USD).

The good thing about using a wide-angle security camera is that it can show all or almost all of a wargames table in a single screen, and that the lighting demands are moderate because of the built-in low-light features. The monitoring software usually allows for moving the camera and zooming (a kind of PTZ, to be sure, but one which does not provide the same quality as the cameras intended for high-end video conferencing).

The quality of the image you get from these cameras is not great, however, when compared to the cameras in most smartphones. The pictures here show you the difference:

The tabletop as viewed through the security-camera monitoring software. Note the "1:1" and "PZT" buttons at the bottom of the screen to the left. These are 28mm/1:48 miniatures, and the image quality is acceptable, but not great. This is literally what players will see when you share your screen during play.

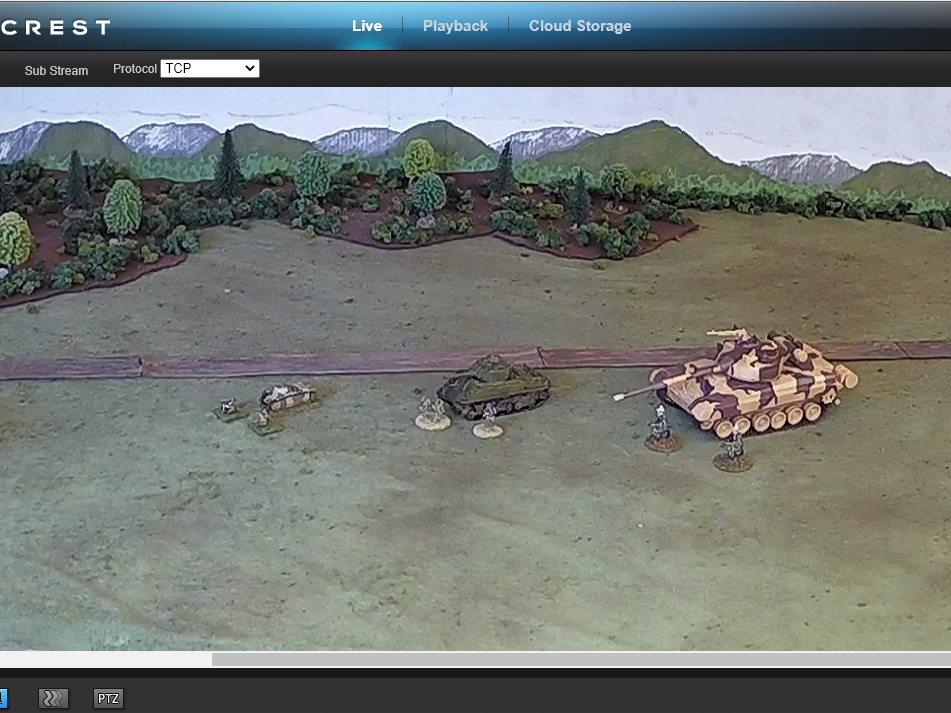

By way of comparison, here are some 28mm miniatures seen through an iPhone 10 camera. The difference in quality is noticeable (but so is the difference in price!)

Further, the picture from a wide-angle camera will fish-eye unless you set it to a 1:1 ratio (there is usually a button for this on the monitoring software). The set-up can be a little tricky: when you set it up you have to plug the camera into your router with a cable, and then use a device to configure it, after which you can disconnect it from the router and access it from the device (or a PC) wirelessly. There will be instructions with each camera telling you how to do this. If you want to access it from a laptop or desktop computer, you may need to install a plug-in from the manufacturer's website on your PC, and follow more directions. (In my experience, it is easier than programming a VCR, but harder than falling off a log. You do actually need to read the manual and follow directions.) Each camera will have a different set of instructions, but before you buy you will probably want to make sure that you can monitor it not only from a smartphone or tablet, but also from a regular PC.

Security cameras will generally need to be set further back from the table than smartphone cameras. To view an 8-foot wide table, my camera is set back about 4 feet from the near table edge, and about 2 feet above the surface of the table on a tripod. (The tripod is a regular one - the camera just screwed on like any other camera would). This means that you will have to think about the space you have to set your wargaming table up in, and how big a table you want to use when running games.

In terms of the diagram in the preceding section, the dotted line connecting the Game Master's computer to the camera is actually a wireless connection, running locally at their location. There is generally no physical cable involved. For a USB web cam (like those used for high-end video conferencing), a cable could be used to physically connect the camera to the computer.

If money was not an issue, my preference would be to spend a few hundred dollars on one of the new USB video-conferencing cameras with EPTZ. This would simplify things: just plug the camera into your computer, install the software to run it, and you would have good image quality and the wide-angle needed to cover the whole table. Many gamers will find the cost of such a camera prohibitive, however: the wireless security camera provides a reasonable option for those who do not own smartphones, but either way there are trade-offs.

There are, of course, ways to get creative using more than one camera - we will look at some ideas here (and some other tricks) below. First, however, we will discuss some other relevant topics.

Although the tabletop is basically the same as you would use for any miniatures wargame, there are a few specific things which deserve mention. While there are no hard-and-fast rules, we have identified some helpful approaches, and found that other gamers who are running remote games like this have independently discovered many of the same things.

You may have noticed from the pictures above that they all have something in common: a back-drop. Most miniatures wargamers do not use back-drops, as they limit access to the tabletop, and players typically sit across the table from each other, where they can most easily reach their own troops. When players are accessing the tabletop remotely, however, and viewing it through a camera, things are different.

The main reason for having a backdrop is to make it easier to see the tabletop. Most wargames rooms are full of shelves of stuff, and this can make it difficult for remote players to focus on the tabletop. With a few cardboard boxes and a bit of paint, it is easy to make a backdrop which hides the mess from players, and serves to frame the action. Backdrops do not need to be fancy, but they do perform a very useful function. They should be kept fairly low in relation to the tabletop, however - 18 inches is a good height - so that it is easy to reach over them to position and move troops.

In a normal miniatures wargame, players are free to walk around the table and look at it from whatever angle they wish. This is much less possible in a remote game conducted through a camera. One consequence of this is that the amount and positioning of terrain on the tabletop should reflect what players can and cannot see. In general, having relatively sparse terrain is a good idea: it can be quite frustrating to be giving orders to troops which you cannot see. If there is a primary camera angle, then taller and more obscuring terrain can be kept to the back and sides, leaving the main area of play more open.

Another consideration is the camera angle down onto the tabletop. While having a "birds-eye" view from straight above might seem like a good idea, it is also very unnatural for players. We are used to looking at the tabletop from above, but at an angle. We have found that trying to reproduce this perspective is the most satisfying approach. Games with more terrain may require a steeper angle, and games with little or no terrain can use a shallower one. Game masters should experiment with this before play starts, until they are satified that players will have the best possible view of the game.

One last consideration is that communications between players and the Game Master will be spoken, with only the Game Master able to move figures. It is very helpful to have some landmarks on the board which can be used for reference (e.g., "move them up to that white rock on the hill", etc.) and to distribute a map of the tabletop with named reference points and compass directions on it before play starts (see below). The table will have a back and a front and a left and right when viewed from a fixed point, and this can also help in communications between game master and players.

Game Masters should also bear in mind that players cannot always see updates in real time (the web may cause a camera lag of a few seconds), so that pointing at things while talking may not work the way they expect. Judging distances over a remote camera can be hard to do accurately, too. Players should be free to ask questions about distances, since things which they could see for themselves in a normal game may not be as visible through the camera.

Many people have experimented with games that use a grid, which is clearly marked on the tabletop. This can also serve as a good mechanism for helping players and the Game Master communicate, and to assist in understanding the tabletop distances.

This picture shows the way the tabletop is actually set up for play. The steep angle down onto the tabletop does help to show the figures and their relationship to the terrain, but may not provide the best gaming experience for players. During play, the camera would be zoomed in to give a better view of the figures, and to cut out all the surrounding (and distracting) mess.

There are a large number of reasons for preferring one scale of miniatures over another, but when it comes to remote gaming with miniatures, the rule is a simple one: bigger is better. In general, a game which plays well with 15mm miniatures will work better in 25mm when played remotely, and many 25mm games would probably work better in 40mm or 54mm. The smaller scales become very, very small, and detail and colors become impossible to see.

The picture below gives you some idea of how this works:

Figures in 15mm, 25mm, and 54mm scales, at a normal zoom for viewing the whole of the tabletop during play, taken with a security camera. The figures seem much smaller than they do in real life. 6mm figures would be indistinguishable from dust-motes! A better-quality camera, and zooming in closer to the figures will of course show better detail.

Something which we have found useful during play is to use flags as unit identifiers, for those games where record-keeping or orders systems require it (the flags can be seen in some of the photos above). While ugly, they do allow players to determine where their units are. Similarly, we no longer use casualty markers, but instead use blobs of cotton wool or brightly-colored chips to indicate disorder, etc.

The sad truth is that you simply cannot fully appreciate the excellence of a well-painted miniature when gaming this way. Even the larger scales give more of an impressionistic view of the battle. (Of course, gamers often don't really look at the miniatures very closely when they are playing, in any event. And when the pandemic ends, you will still have all the figures you painted for closer examination then!)

Given the limitations of gaming remotely, it is clear that some games are better-suited than others to this format. There are several things we have learned about which games do and do not work well. Further, the way in which scenarios are designed can have a huge impact on whether a game is successful.

Different groups of gamers have different tolerances: some gamers may prefer fast-play games, while others may be happy with a slower, more complicated game. This is no different when running games remotely. What is different is that the overall pace of any game will generally be slowed down, if only by the fact that all communications are running through a conferencing system like Skype or Zoom, and by the fact that understanding what is happening on the table is not immediately clear for all to see, as a result of the camera.

One big consideration here is how reliant the game system is on the exact position of troops on the tabletop. If a difference in facing of a few degrees exposes a unit's flank, it may not be obvious to players looking at the table through a camera whether their unit is or is not exposed. Unless they ask the Game Master, they may have intended to do something, and not realize that - judging from what is on the table - it has not actually been done, etc. Players and Game Masters alike need to be forgiving in such situations. Some games have a heavy emphasis on such positioning, and on exact range measurements, and these games can be slower and less fun to play remotely. We have found that if players state their intent when moving a unit, then it is clear to other players, and any unintentional mis-placement can be more easily handled. In general, the more "finicky" the game system is, the slower it will play, and the greater the opportunity for misunderstandings of this type.

Many people have used remote miniatures with games that are grid-based, and for which the grid can be clearly seen on the tabletop by players. This has the advantage of making the position of units and the calculation of ranges easier for players to see, but limits the range of games which you can consider. Communications are also eased if the grid coordinates are known to all participants, so that locations have reference numbers.

Depending on how dice rolling is handled (see below), this is another aspect which can impact game play. A heavy reliance on dice can become cumbersome. Computer-assisted games which already employ centralized moderation by a Game Master, and which do not involve dice rolling, are a good fit for remote play.

Games which use an I-go-you-go kind of turn sequence can also be problematic: players cannot side-chat easily, or spend their down time wandering around the table and admiring paint jobs and terrain, so players will become bored more easily if they are not participating for prolonged periods of time. The maximum number of gamers is more limited in remote games because of this, too. We like games which have frequent interaction between players during each turn, and have found that games with even 5 or 6 players can present problems with some people sitting and doing nothing for prolonged periods. The optimal size for a game is generally held to be 2-4 players plus the Game Master.

Cooperative-play games have also been found to be well-suited to a remote miniatures approach. This is in part because players are not set directly against each other, and differences in how they are viewing the table (one through a large screen on a PC, another on their smaller smartphone screen, etc.) do not create unfair conditions. Similarly, die-rolling using a trust system becomes non-problematic (see below). Coop play games are also good because orientation in terms of the "front" and "back" of the table, which can affect how well players see what is going on, are rendered irrelevant (all players can be given the best remote view, toward the front of the table, because the Game Master can easily see everything, and run enemy troops toward the back). This fact also suggests that the limitations of what players can see could be used to introduce realistic "fog of war" effects.

Choice of scenario is almost as important - or even more important - than choice of game. We have found that smaller scenarios work best. The rule of thumb is to reduce the size of armies by half. Considerations of table space are also paramount: if you are using larger figures than you normally would, distances on the table may also change, reducing the overall size of the battlefield. When we use 25mm figures to run 15mm games - which has been pretty common - we double all movement rates, ranges, etc. This makes the game easier to see, but cuts table size in half. This reduction in size impacts scenarios significantly.

We have found that gamer fatigue can be an issue as well. Games which go for more than 2 or 3 hours can start to wear on players and Game Master both, partly because of the constant talking on the Game Master's part, and partly because using conferencing software is innately more tiring than face-to-face social interaction.

The kinds of scenarios you choose to run may also change: any scenario which hinges on hidden deployment, surprise, or limited knowledge of the battlefield is actually easier to run in a remote-miniatures format than in a face-to-face one. Players cannot look over at the next table to see how many units of the enemy are there, waiting to be deployed, and it is easy for the Game Master to mis-direct players attention from some portion of the table top by simply not showing it to them. It is also possible to use direct person-to-person chat exchanges on Skype and Zoom, which can be conducted by the Game Master and specific players, completely unknown to other participants. These aspects of the format can be used creatively when designing scenarios, for conducting hidden movement and so on.

There is no simple formula for identifying what games and scenarios are best for remote play, but there are significant differences with face-to-face tabletop games. Scenario designers and Game Masters need to think about these topics to produce the most enjoyable games possible, especially given that the format has a lot of other limitations. (Players will put up with a lot of disadvantages if the game itself provides a unique experience: think about the "periscope" games people sometimes run, and you will get the basic idea.)

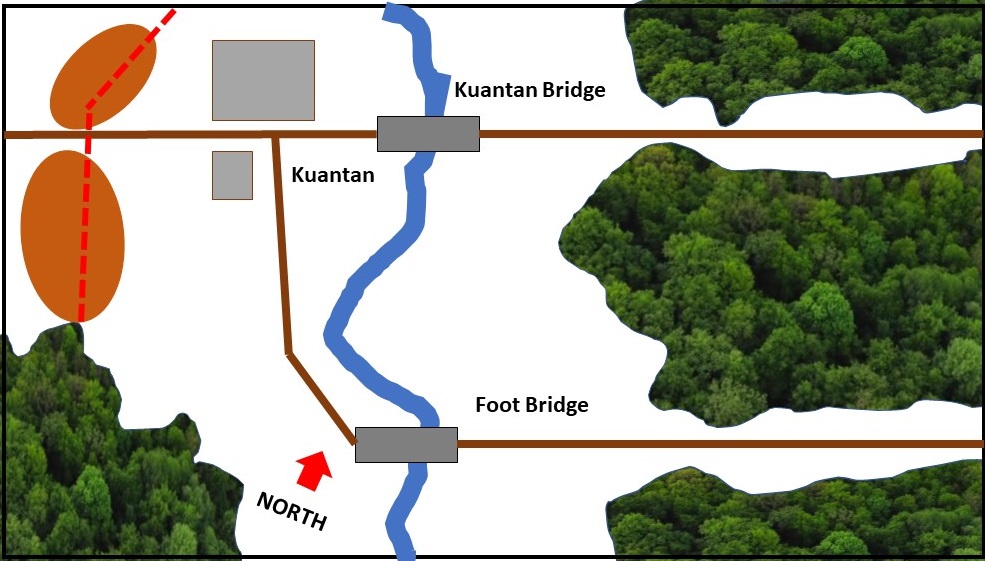

People with experience running convention games have long understood that having scenario write-ups and player sheets can help orient game participants, and get them quickly up to speed. This idea becomes even more important for remote gaming. We have found that it is best - unless scenarios are very simple - to send out a write-up including a map, orders of battle, and other scenario information before play.

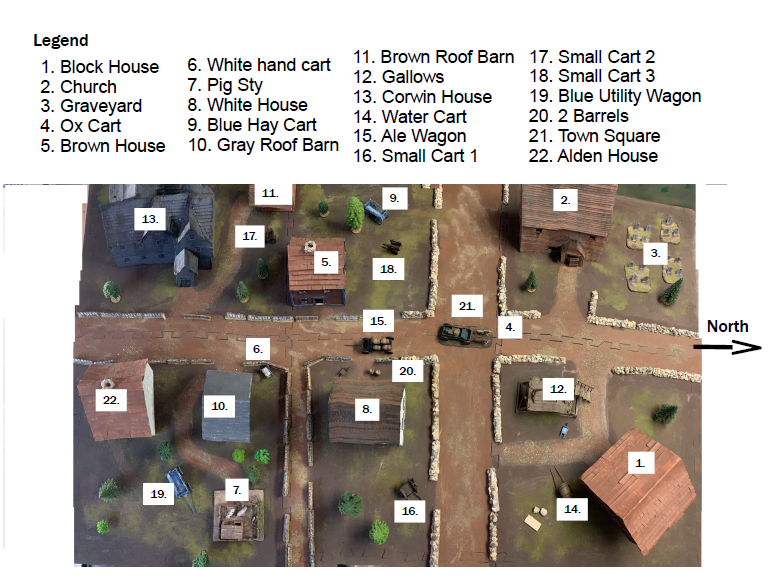

Perhaps the most important thing is that - in any game with a reasonable amount of terrain on the board - the players are given a map, and any recognizable features are given names. These can act as reference points during play. If there are three towns on the table, it is much easier to say "move just to the south of San Miguel" than it is to say "move to the south of that town which has the church with the steeple on it - no, I mean the other town which has a church with a steeple on it. What? That isn't a steeple? (etc.)". Maps which give references to significant locations (assigning letters, etc.) can be very useful, and speed communications and play.

We often use Powerpoint to create simple maps, and sometimes take an overhead shot of the terrain and then superimpose labels on it. It is generally a good idea to clearly indicate compass directions on maps, too - something which is a lot less important in face-to-face play.

A map, created using Powerpoint and distributed before remotely playing a fictional Malaya 1941 scenario. Place names and compass directions are clearly marked, and explanation of terrain and features was also provided in accompanying text (the dotted red line is a line of fortifications, etc.).

A map for a skirmish game, created by over-laying labels on an overhead picture of the table. This is a terrain-intensive board, so all significant locations have been numbered and a legend provided. Without this kind of map, the game would have been chaos!

We have already pointed out that games should be fairly short, and doing set-up of forces before the game starts - if possible - is a good way to limit down-time. Often, we will send out orders of battle and maps, and whichever player has to set up first can communicate that beforehand by e-mail or in a separate phone conversation. This becomes doubly important when scenarios involve hidden deployments. To the extent possible, players should be given scenario information - including maps, OBs, and victory conditions - before play starts, so that any planning by one side or the other can take place before everyone - the enemy included - is dialled into a call.

Testing cameras and table set-up is also a good practice for Game Masters, to make sure that everything is working before play starts. Needed units can be laid out, along with markers, dice, rulers, etc. The Game Master is going to be doing a lot of running around and talking, but when they are not present to conduct the game, then nothing is happening. If everything the Game Master needs is organized and laid out, this minimizes down-time for everyone.

Another important part of pre-game set-up is to ensure that all participants are familiar with the conferencing software, and any needed accounts and connections are made before play starts. Few things are more mind-numbing than listening to a Game Master talk someone who is not tech-savvy through a Skype installation on an antiquated version of Windows in the background, over the phone, while you are waiting for a game to start. (Trust me on this one!) A lot of time can be wasted sorting out technical challenges, but it can - and should - be done ahead of time.

Once a regular group of players gets used to using Skype or Zoom (etc.) then these problems disappear, but they should be borne in mind when bringing new players into the group, or when running virtual covention games.

There are several topics which also deserve some mention, resulting from our experiences running games, some fairly obvious once you start doing it, and some perhaps not-so-obvious. Many wargamers are middle-aged Luddites, and they have not been exposed to conferencing software before: for players who use it on a daily basis (and their number is growing during the pandemic) things seem obvious which, to others, are not obvious at all. As a general rule, patience is called for.

Skype is the platform we use most often, not because it is the best, but because it is free, and everyone who has a modern Windows machine already has it installed (if you are running Windows 7 or earlier, you will need to download and install it, but it is still free). Skype is available for Macs and mobile platforms as well. There are many other options, but the most common one is probably Zoom. Zoom is also free, and requires no installation, but the free version cuts off any meeting of more than 2 people after 40 minutes, requiring everyone to dial back in. A paid subscription to Zoom is not terribly expensive, and players may find it is worth investing in (or may already have access to a paid Zoom license.) If the person hosting the meeting has a paid Zoom license, no one else needs to have one - only one license is needed for the group to have an uninterrupted call. Both Zoom and Skype are very familiar to people who use such platforms for business purposes, which means there is already a fairly large population of gamers who know how they work.

There are many other platforms out there. Discord is extremely popular among younger gamers, being the ubiquitous platform for online video-gaming against live opponents. To get the most out of it, you have to do an installation, but it is free, and there is a web version. Facetime is a nice application, but (in the long tradition of Apple standing in the way of any human progress not running on devices which they produce) it does not work on anything but Apple hardware. Since a lot of gamers (and a lot of the general population) use Android devices and Windows PCs, this makes it a non-starter for many of us.

We will look primarily at Skype here, and mention Zoom, but you may find that a different platform is better for your own purposes. Discord is perhaps the most appealing alternative, but the list of possibilities is a long and growing one.

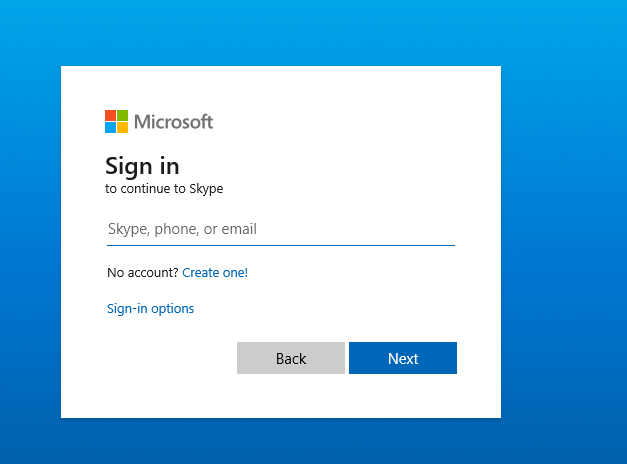

Skype requires that everyone on a given call have an account. Since most Windows users already have a Windows account with Microsoft, they may already have a Skype account (if they can remember their password, which not everyone does). You can also go and - using the Skype interface - set up a new Skype account (or more than one) for free. The picture below shows what you will see if you launch Skype on your machine for the first time:

By clicking on the "Create one" link, you will be lead through the process of setting up a new Skype account. Once you have gotten one, you will be assigned a Skype ID which is typically an unmemorable string generated by the software. People can use this ID to connect with you if you can find it and send it to them. They can also search (using Skype) on your name, but not very many people have names which are not already being used. Sorting out which Mike Jones you want can get messy - you can use profile images and locations to help with this process, but it isn't always easy. (There is an easier way to connect, too, as you will see.)

If you do have someone's Skype name or ID, you can send them an invitation to connect on Skype, which will send them a textual "chat" message in Skype. When they go into Skype and accept the invitation, you are then "connected" and will appear in each other's Skype contact lists. This makes it easy to find them when setting up games.

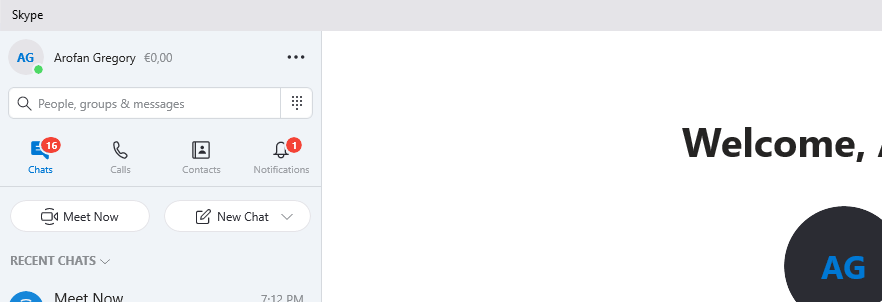

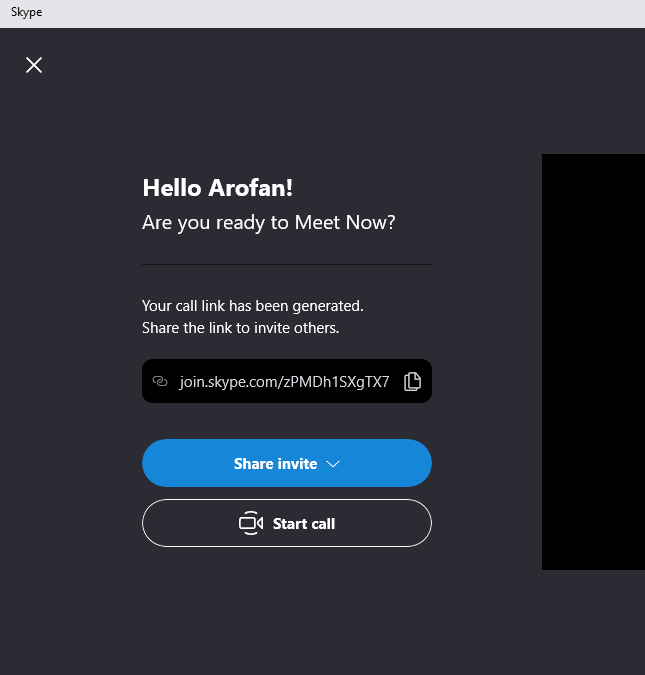

There is a simpler way to do this, however. Skype has a feature called "Meet Now," as shown in the picture below on the left-hand side:

If you click on this button, you will see the following screen (although hopefully it will be using your name instead of mine!):

This lets you do two important things: start the call, and invite people to join it. You start the call by clicking on the "Start Call" button. But if you want other people to join you, you will first have to use the "Share Invite" button. If you click on this button, you will have the option to invite Skype contacts, to send send the link via e-mail using Gmail or Outlook, or to copy the link, which will let you paste it into the text of an e-mail you can send using another e-mail program, or into any other place that posts links (Facebook, etc.). This can be done a few minutes before the game starts.

Anyone who receives an e-mail need only click on the link, and once they have signed into Skype they will be added to the meeting.

On a last note, Skype can get very hard to manage if players individually call the host of the game on Skype, as the Game Master then ends up with a large number of disconnected, simultaneous Skype calls. We have found that letting the Game Master drive all communications proactively is best: players should simply send them a Skype text chat or e-mail to indicate that they are ready and waiting, and let the Game Master e-mail them the meeting link, or include them directly through Skype using their Contacts.

Zoom also requires that the host of the meeting have an account (you can sign up for free on the Zoom site). Once logged in, you can schedule a Zoom meeting This will also generate a link wich you can send to the participants in an e-mail. By clicking on this link, they will be pulled into the meeting if they accept the simple prompt which asks if they are OK with doing so.

Zoom meetings are simpler to set up and manage, but will time out after 40 minutes if you have a meeting with more than 2 people, and are using the free version. If you are OK with this, players can just use the same link to start another meeting for another 40 minutes, or you can pay the moderate subscription fee which a license requires to be free of interruptions.

In order to see the table, the camera image must be screen-shared with everyone in the meeting by the meeting host (the Game Master). They can do this once the meeting starts by using the "Share Screen" icon in the lower right-hand corner of the Skype screen, as shown below:

By clicking on this link and the following screen, whatever is shown on this computer will now be shown to the other participants. Once sharing is working, the host shifts their computer or device to show the camera view of the tabletop, and everyone should be able to see it. Note that there is a bit of a delay. Also be aware that all participants in Skype can share their screen, but that you really only want the host (the Game Master) to do it, otherwise the image of the tabletop gets smaller and smaller! Any given participant can only share their local screen - they cannot "help" the host to share what is only visible on the host's computer. (You can get some incredibly psychedelic "house of mirrors" effects by screen-sharing a machine that is screen-sharing the machine that is screen-sharing it's screen, but this kind of thing - while extremely groovy - will definitely not enhance play!)

Zoom uses a very similar mechanism, but by default limits it to only allowing the host to screen share (although the host can pass their status as host to another participant). We will not go into details on Zoom here.

People who use Skype and Zoom and similar platforms learned long ago that there are some basic rules of etiquette that don't apply anywhere else. It is important that these be observed by remote gamers. The primary one here is: Don't talk too long!

This may seem very strange, but it is a fact of the technology that - unlike telephone communications - when one person is speaking, other people cannot easily be heard, and in some cases cannot be heard at all. You can literally lock everyone else out of a conversation simply by talking without pause, and they have no way to interrupt you. When two people talk at the same time, no one can understand anything said by anyone. You have to leave breaks in your speech, in order to allow others to respond or break in. Being long-winded without pause - and a remarkable number of wargamers are this way, as a consequence of being passionate about the hobby and generally very social - is the cardinal sin. This is weird, but it is also true. Take pauses when you speak online.

Another important rule is to mute your microphone if you have a lot of background noise going on, when not actively speaking. For technical reasons having to do with how these platforms filter different frequencies to emphasize the human voice, eating chips (or anything else) out of a foil bag produces an incredible tsunami of horrifying noise for everyone else: put the chips in a bowl! (And even then, chewing and crunching is something you should generally do on mute.) Background noises can be magnified in various and unexpected ways. Players should feel free to politely comment when there is a lot of background noise, as it causes everyone to suffer except the person who is causing it. They, in turn, are generally not even aware that they are inflicting this on other people, and usually do not wish to be doing so.

Similarly, if anyone's mic volume is too high or too low, this should be politely commented on. It is not rude to do so: there is no way for a participant to know if they are too loud, or if they cannot be heard easily. Asking about such matters is routine as a game gets started.

There are some other things you will learn as you go: when gaming, gestures are invisible to others, so pointing at things doesn't work. Also, visuals may lag behind spoken communication (leading to the sometimes amusing "hand of God" effect where the Game Master can actually change something on the tabletop and be gone before anyone sees that it is happening).

It is counter-intuitive when people who you are talking to are actually seeing a different version of what you are looking at, and this needs to be taken into account. The Game Master, especially, must be aware that what players see is not at all what they are seeing: they have the table in front of them, but players only see what the camera is showing them. Players must learn to speak up politely when they want the Game Master to show them something, and not feel that they are being rude or pushy. In general, whoever is making a move has both the "mic" and the priority when it comes to adjusting the camera's view, since it is their move, and everybody has to take turns.

It is normal to have a face-cam showing each participant in an online conference call, but we find that it is usually a good idea to turn player video off. Usually, this is a matter of maximizing available bandwidth to show the table, and to allow for better voice quality. This may or may not be a factor for any given gaming group, depending where each participant is connecting from, but if any player has low bandwidth, shutting off individual player video cameras can help. You should not feel offended if you are asked to turn off your video, nor should Game Masters feel that they are being rude if they ask this of players.

In our experience, as long as people are patient and good-natured, you will quickly learn how to behave in remote gaming situations. At first, however, it can seem a bit strange. It is quite different than gaming face-to-face. The good news is that a remote gaming session retains much of the social aspect of face-to-face gaming: when you sign off at the end of the evening, you feel like you've gotten a game in with your buddies, which is something a lot of us had been missing when the pandemic locked us down.

Some gamers find that rolling their own dice is an important part of gaming. It serves as the ritual which connects them with Fortuna, and is an important part of play. Other gamers are indifferent, or even prefer to have others roll their dice, through a (probably correct) conviction that the Gods hate them. It's a personal thing. We have tried a number of different systems for rolling dice, and have found that the following ones work well:

The Trust System: Tell players what dice they will need to have on hand during play, and let them roll and report their own dice. Anyone who cheats is acting in an ungentlemanly fashion. In cooperative-play games, they are also only hurting themselves, since it just takes the challenge out of it, which is the whole point. We often let players roll their own dice or have the Game Master roll for them, based on each player's personal preference.

Let the Game Master Roll: This is the fastest way to do it, and it guarantees that everyone will have the same basic chance of good or bad rolls, insofar as these are based on karmic influences. This can be done in combination with player rolls on the trust system, as noted above.

Use a Multi-Player Virtual Die-Roller: Many online gaming platforms have virtual die-rolling, where everyone can see each player's rolls. The one we use is hosted at our Application of Force site, but there are other options. This technique is fun because players can see each other's rolls, which is sometimes quite amusing indeed.

Play Computer-Assisted Games: Games which rely on computerized randomization simply avoid the issue altogether (quite aside from being well-suited to the style of moderated play which remote miniatures gaming demands).

Some people like to show a dice tray on-screen during play, either at the player end or on the Game Master's table. Some remote set-ups even have dedicated cameras showing nothing else. This is a matter of taste, since some people like it, while others see it as an annoyance which slows play. Regardless, it should not be seen as an absolute requirement, as it does complicate the overall set-up for cameras and conferencing, and is not strictly necessary.

Locally, we have come up with a term for that phenomenon where the camera, in process of being shifted, shows a rapidly moving montage of whatever happens to be in front of it, usually including table legs, the Game Master's legs, the floor, and blurry shapes which cannot be readily identified. We call it the "Blair Witch Effect" for rather obvious reasons.

Games will involve shifting the camera, in almost every case - it is simply unavoidable. What Game Masters will often not realize is that this effect can be extremely annoying when it happens too much. Moving the on-screen camera - especially when there is only one - should be avoided as much as possible. If a camera can be rotated in place, so that the view slides across the table, that is best. Some of the locals have started developing set-ups where the entire table rotates on a dolly, smoothly, so the camera doesn't have to move at all. This has the effect of letting the table "pan" across the screen, which is much less disorienting.

As a general rule, if you only have one camera, it should have - to the extent possible - a fixed relationship to the table, and move as little as possible. One major advantage of security-type cameras is that they allow for panning and zooming without any camera movement at all - we routinely shift the camera view from left to right across the table during play, and it is not disruptive. Having a fixed view of the table also establishes a front and back, which can help in communications about positioning troops and other game actions.

Another unfortunate and often-unavoidable phenomenon is having to look at the seat of the Game Master's trousers while they are adjusting figures on the tabletop. On a small table, this can be completely avoided - on a larger one, it may be inevitable. To the extent possible, this should be avoided, and gaming set-ups should have low backdrops and walking space enough to permit placement and movement of figures without the Game Master in frame any more than is necessary. (For those cases where it is unavoidable, it has been suggested that an iron-on "Hello, Kitty!" patch could be used to good effect.)

It is a good idea for Game Masters to participate as players in remote games, in order to develop an understanding of what their players are experiencing in their own games. Unlike face-to-face games, the two experiences can be quite different, and sometimes in unexpected ways. You can think of the gaming table as a movie set - a perspective which isn't very relevant to normal games, but begins to apply when you start using cameras.

Up to this point, we have been discussing a very basic approach to using cameras and online conferencing software, with the idea of helping people get started. What we have found, however, is that once you have run a couple of remote games, you start realizing that without too much additional equipment or complication, you can improve the whole experience considerably. There are some different ideas about how this can be done, and it continues to be a lively topic.

A couple of useful techniques have emerged which are worth sharing: the use of a dedicated connection for the camera, and the use of multiple cameras. We will look at these here.

When a single device is used to show the tabletop camera, and to screen.share it with players, the Game Master is only able to see the camera's view of the tabletop, and not an actual view of what players are seeing. These two are not the same thing: the Game Master sees directly through the camera, where there is better detail, and the picture is larger. Players see a picture of the Game Master's desktop, embedded in a conferencing app, which uses screen real estate for some other purposes as well. It is very useful for the Game Master to be able to see what players see during play.

We now have a simple solution to this problem, although it involves the Game Master using more than one device. Instead of having a single device connected to the camera, which is also used by the game master to speak to the players, we have a dedicated device for each function. Here is a revised version of the diagram we showed at the beginning of the article:

Here we see a set-up where the machine which is attached to the tabletop camera has its own account on the conferencing platform, and is invited and connected to it like any other player. It is this machine which is screen-shared with the rest of the participants. Its microphone is muted.

The Game Master himself, although sitting in the same location as the camera, table, and the camera-device, has a second device which is used to connect with its own account. This is the account the Game Master uses to speak to other participants. Using this device, the Game Master sees exactly what all the other players are seeing, making it easier to understand what they are talking about, and to spot when something that shows up clearly on the local camera cannot actually be seen by the players, etc.

This may sound like a minor thing, but it can make a big difference to how well Game Masters can manage the entire proceeding, and it is highly recommended.

Another important technique is the use of multiple cameras. Many experienced Game Masters who have been doing remote miniatures gaming for a long time (and we have met a few, although not very many) will use as many as 4 or 5 cameras to view a single tabletop during play. These cameras can be used for different functions, and can give a much more detailed view of the game than anything we have discussed so far.

A basic multi-camera approach is to have two: one giving a general overall view of the table (a security camera would be good for this), and another giving a close-up view of a particular portion of the table (a smartphone or high-quality web-cam on a tabletop tripod is good for this). The close-up camera can be moved as needed during play, and the other camera can be left showing a static view of the table. You can also simply focus multiple cameras at different parts of the table, and from different angles.

There are several challenges when doing this. One is to make sure that the Game Master can control which cameras are being shown at any one time, because if multiple sections of the desktop are showing different parts of the table to players, this can rapidly become confusing. If you think of players as watching a movie, you will get a sense of how people orient themselves visually when interacting with screens. Too many different views which do not have an obvious relationship to each other can be very confusing to viewers.

The way in which the cameras are managed by the Game Master and shown to players can have a big effect on this technique. There are dedicated software packages which will allow the Game Master to combine several camera views at once on a single screen, which can then be shared with players. This is a good approach, because it gives the Game Master absolute control over which views appear to players where. However, it requires the use of dedicated software of a fairly sophisticated variety.

A less-controlled approach involves having multiple cameras, each with their own dedicated device, connected to the conferencing platform with their own accounts. It is possible in Skype and on some other platform to have multiple simultaneous screen-shares. The problem with this is that each player may see these arranged differently on their screen: what is a left-hand panel on one player's screen might be a right-hand panel on anothers, and vice-versa. This can increase confusion and make the game less enjoyable.

Multi-camera techniques can provide a much better gaming experience, but they do require the Game Master to have a tested set-up, and to be able to use all the involved software effectively. This may be too tall an order for many wargamers. It certainly goes beyond the intended scope of this article.

That said, members of the Virtual Tabletop Gaming Facebook group do use multi-camera set-ups to very good effect (see the next section).

For most of us, remote gaming with miniatures and cameras is a new thing, and would not even have occurred to us without the pandemic. But we have to do what we can, given the circumstances, and - having invested huge amounts of time, money, and energy into our miniature armies - it seems a waste not to use them. This is a new format for miniatures gaming, but, like miniatures gaming throughout its history, it will grow and evolve. Miniatures wargamers have never stopped playing with new ideas and new techniques, and there is no inherent reason why this type of gaming should be any different. All we can do is try, and see what works and what doesn't.

If you are interested in pursuing this type of remote miniatures gaming, you should join the public Virtual Tabletop Gaming group on Facebook. The community there is very open to hearing about new ideas, and is full of people who will actively support gamers who want to give it a try. There have been several recent events which will help illustrate the kinds of things they do:

Let's Roll: When Huzzah!, the preminent regional miniatures wargaming convention in New England, was cancelled, some enterprising members of the community pulled together a very successful virtual convention in a matter of weeks. There were 200+ participants, and many games, several of them featuring remote miniatures in the style we have been discussing.

Cyber Wars: It was recently announced that the Historical Miniatures Gaming Society (HMGS) would run a virtual con, to help fill in the space left by the cancellation of their normal conventions. They have been active in discussions with members of the VTG group to find out more about how to make this happen.

Remote Miniatures Round-Table: The VTG recently had a round-table on the topic, to learn from people who had been running remote games with miniatures, and to help educate people who were interested in learning more. This type of event is likely to be repeated in the future.

GMing a Virtual Game: A plan is being formed to organize a day when a group of Game Masters can each take turns showing the set-ups they use, and running a turn of a game and then getting feedback from others, acting as players. It can be daunting to run a game without having some experienced people take a look at it first, especially in a convention setting, so this was seen as a way to help people get organized and gain a little confidence.

In General: There are many members of the group who regularly run games, and who are happy to have new players, and to extend a hand to those who are learning to run games this way. Anyone who is interested should inquire on the group. It is a genuinely supportive community.

While many people think of remote miniatures gaming as a stop-gap, to fill in the void left by the pandemic, it has occurred to more than a few of us that there have been some unanticipated benefits. One of these is that people who we would normally game with only once or twice a year, at cons, can now become part of our regular routine. We all have gaming friends who live in other parts of the country, and it's great to be able to game with them more regularly.

Another unexpected benefit of this type of gaming is not having to travel. In my experience - and for some other members of the group - we are actually gaming far more often now than we did before the pandemic. Instead of having weekly club games, and attending a few conventions and game days over the course of the year, we find that we are gaming several times a week. When you do not have to travel, and the figures do not need to be packed in boxes, it is a lot easier to run games. (And besides, a lot of people are sitting around at home, bored!)

I predict that this type of gaming will become much less popular when the pandemic subsides and we can get back to normal face-to-face gaming. It's almost a certainty. But I have another prediction as well: it won't ever entirely go away. Once we are equipped to run games with remote players, and comfortable with the technology, we will probably continue to do it just to stay in contact with our remote gaming buddies. Why wouldn't we?

It may seem a little daunting to those who are not comfortable with the technology, but like a lot of things in the modern world, once you start it becomes pretty easy. There are a lot of people who are happy to help their fellow gamers, perhaps in the hope that they will find another like-minded person who can help them while away their leisure hours in the way they like best. It does take some effort, it is true, but not an overwhelming amount. Many of us have found that it is very well worth it, adding a new dimension to hobby we have always been passionate about.

Ultimately, it is up to individual gamers whether this style of remote gaming is worth pursuing or not. It can be done without too much difficulty or expense, and - although perhaps not as much fun as gaming face-to-face - it can certainly help to fill in the gaps forced on us by the pandemic. It even allows us to game with people we could not otherwise meet, even without the lock-down, due to the constraints of time and distance.

In the end, it comes down to this: you can have all of your miniature armies stand down for the duration of the pandemic, if you want, but you can be sure that ours will not. Instead, they will be marching into battle!

Copyright (c) 2020 by Arofan Gregory. All rights reserved.